As of late, there has been a significant amount of griping

surrounding the plight of the “millennial” generation. I figured as a

millennial myself, I might as well throw my two cents in and share my

reasoning for why I vacillate between semi-to-self employed, am 60,000 dollars

in student debt, and have a credit score I feel uncomfortable sharing (ask me

in six months…)

Some critics believe the plight of the millennial is rooted

in their wild optimism, lofty expectations and over inflated feelings of self

worth. I would contend that the millennial generation, though falsely

accustomed to instant gratification, has actually mastered the art of

self-deprecation more than any prior generation. I would also contend that wild

optimism and lofty expectations are in actuality the silver lining of the

millennial storm clouds. Let me reiterate that a “silver” lining must been

viewed as “silver” rather than wishfully morphed into “gold.”

I started out as a Type A. Today, I would say my motivation

and general person lingers more in the mid-alphabet. Initially, I mourned the loss

of A. I began high school with one goal and one goal only, Stanford University.

I opted to go to a different school than all my friends my freshman year in

order to prep for this goal. I began rigorous SAT prep, I endured many itchy

days in plaid polyester, I was a three sport athlete, I took AP/IB classes, I

ate organic, I had a personal trainer, I participated in Model United Nations,

yearbook staff, French club, etc. etc. I wanted the accolade and adornment of

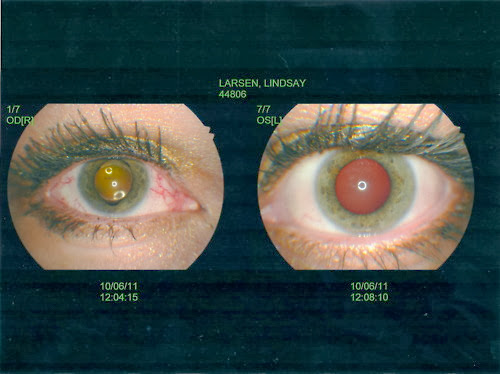

Ivy (or the west’s version of it) more than anything and I didn’t have a clue why. When the cancer storm hit my junior year I rationalized that I would only

be out of school approximately a week to recover from the surgery and I would

be able to do my schoolwork. One week became six, and I was unable to see for

most of them. When my vision was

restored and I was able to return to school, I struggled immensely. I failed

daily quizzes almost every other day. I went to see a neurologist and began to

undergo evaluation from educational psychologists. It was soon revealed that I

had suffered a TBI from the surgery and had lost my working memory. My IQ test

results showed a 40-point deficit from where I originally had tested. I

discovered I had lost my working memory approximately a week before I was

supposed to begin AP exams and a month prior to taking the ACT/ SAT. I

completed the year with several incompletes and spent the majority of my summer

attempting to catch up. As I began my senior year I still held onto the hope

that I would recover and somehow be able to generate the grades and test scores

in order to attend my dream school. It didn’t happen. My neurologist assured me

that I was young enough at the time of injury for my brain to recover. He said

it would make new connections and create new neurological pathways, but it

would never be the same as it was prior to the injury.

I was admitted to a good college not far from home and

grappled my way through the first year with a compromised working memory. I

completed my first year with a 3.1 GPA.

As I continued to study, I became more and more drawn to the

arts. After the first semester of my sophomore year of college, the tumor

returned and I had to take a leave of absence from school once again.

Because of the rarity of the tumor I had to seek out

specialized radiation treatment at MD Anderson hospital in Houston, Texas. Not

only did the radiation therapy provided at MD Anderson save my life, MD

Anderson was also the place where I was introduced to art being used as a

mechanism for healing in pediatric cancer patients. When I was given a clean

bill of health I returned to Utah and began participating in as many arts related

ventures as I could. I practiced as an artist individually and also began to do

art with youth in a myriad of therapy and high-risk settings. I was amazed not

only with the therapeutic benefits but also cognitive gains the youth I worked

with experienced. I also saw significant changes in my own cognition and

academic performance. I saw the new brain my neurologist had promised would

begin to emerge.

It took me, the former type A, over six years to complete my

bachelors degree. When I finished up my undergraduate studies, I applied to

graduate school and hoped to pursue a masters of Arts in Education from Harvard

University. This time as I pursued the Ivy, I knew my reasons for doing so. I

knew art had changed my brain, my life and my perspective. I knew I wanted to

bless the lives of others encountering the struggles I had previously endured.

I knew I would receive best education possible for what I was seeking to do.

I was admitted to Harvard at 25 years old, over a decade

after I had started pursuing Stanford. The day I was admitted was as beautiful

and glorious as the day I was told there was no longer any visible tumor on my

scans. When I begin to fret about my employment status, or student loans or

that I am being underappreciated or unfairly compensated, I remember this day.

I remind myself that sometimes things happen a decade later than we initially hoped,

sometimes they happen differently, and sometimes in order for things to happen we

have to be completely demolished, excavated and rebuilt. The education,

opportunities, people and lessons that have come my way are worth every monthly

loan payment. My advice to the millennial generation is to stop

griping. Chasing a vision with integrity, purpose and passion is worth the

moments of monetary discomfort. Trust that your brain, heart and life have the

capacity to make all sorts of new connections and that life eventually will

always rewire.